For Lane Stewart, the phone call from his wife alerted him to what was about to happen.

“My wife worked for Life Magazine,” he says over the phone, “and they had a sportswriter and she says, ‘He just came into my office. He wants to know how to reach Sidd Finch.’

“And I said, ‘Oh, shit.’ My heart dropped into my stomach. Someone had believed this f***king thing?”

Author, George Plimpton

Actually, a lot of people had believed George Plimpton’s April 1, 1985, story in Sports Illustrated that the New York Mets had unearthed a pitcher about to revolutionize the sport of baseball: Sidd Finch was a Harvard dropout who had spent part of his adult life in Tibet, studying to become a Buddhist monk. He was torn between a long passion for playing the French horn and his newfound talent at baseball, which he played while wearing one heavy work boot and a backwards cap.

Oh, and he could throw a fastball 168 miles per hour.

This is the story of how Hayden Siddhartha Finch, concocted by a legendary author and played by a junior high art teacher, captivated the nation and became a Mets icon.

Jonathan Dee, George Plimpton’s assistant with the Paris Review:

George actually got the idea because a paper in England had run an April Fools’ story a year or a couple years before connected to the London Marathon. It said that there was a Japanese entrant in the London Marathon who was under the mistaken impression that the marathon lasted not 26 miles, but 26 days. And so there were people out there looking for him; he had just sort of run into the countryside.

So George was totally fooled by this. The good thing about him is for somebody who lived the kind of life he did, he was very egoless, and the idea that he’d been taken in by this initially just delighted him. He wanted to do something similar himself.

Plimpton had mastered false backstories before. For “Paper Lion,” his 1965 work about attending training camp as a member of the Detroit Lions, he told teammates he had honed his craft as the quarterback of a semi-pro team called the Newfoundland Newfs.

Dee:

He told the sort of outlandish details. It was about a Harvard dropout, Buddhist monk in training who had accidentally mastered the union of mind and body such that he could throw a baseball like 163 miles per hour. I may have been the only one in the office (at the Paris Review) who understood that, you know, that’s very fast to throw a baseball.

Lane Stewart, Sports Illustrated photographer:

I was a staff photographer and had my little specialties. Sports Illustrated had the greatest action photographers in the world — and I was not one of them. I got a lot of offbeat stories. That was my bread and butter.

I read the story and I thought, “My God, this is Joe.”

Joe was Joe Berton, Stewart’s good friend in Chicago.

Joe Berton, junior high art teacher, an authority on Lawrence of Arabia, Lane and I share the hobby of sculpting toy soldiers. When he would need assistance in the Chicago area, he’d give me a call. And then with my love of baseball, we got into a habit of doing spring training every year since he’d usually have a baseball assignment.

Stewart:

I called him up and I said, “Joe, I’ve got this assignment down in Florida for spring training. The Mets have this pitcher in a tent; he’s under wraps down there. It’s a big secret and Sports Illustrated has got this exclusive. The guy’s like a Buddhist monk who doesn’t wear shoes, he’s got a French horn and get this: He’s got a 100-something mile per hour fastball. And you know the weirdest part? You’re going to be him!”

That’s how it started.

Berton:

We had pretty much a one-page printout from Plimpton on what this character was about. We thought it would maybe be a column with a picture down beneath it, not knowing how big of a deal that was going to be or how big of a story they wanted.

Joe Berton (right)

Jay Horwitz, Mets director of public relations:

Here’s what happened: (SI editor) Mark Mulvoy was a good friend with Frank Cashen. Mulvoy and Plimpton came up with this idea about doing an April Fools’ joke, and they wanted to know if the Mets were interested. Cashen said he loved this kind of stuff.

So we sent out a press release to the writers that the Mets are happy to announce we’ve invited so-and-so to be in camp with his 190 or whatever miles per hour fastball. Before the article came out, we staged some pictures that would run with it.

The guy was this tall, gangly guy — like 6-foot-4 and 150 pounds. We had him in this small locker room and all the guys are, “Who’s this guy?” Our new prospect!

Plimpton was also close with then-Mets owner Nelson Doubleday, whose publishing company worked with the author. So Sports Illustrated was given free rein at New York’s spring training facility in St. Petersburg. The Mets even put canvas around a batting cage to preserve the idea they were hiding Finch from detection.

Horwitz:

The players were so cooperative. Lenny Dykstra actually went to the cage and said how good (Finch) was and he’d never seen anything like that fastball.

Stewart:

Spring training, it’s a different world from real baseball. It’s wonderful. We show up and there’s no problem going in and out of locker rooms, there’s no problem wandering around and walking up to people. I had this little idea of the name on the locker, and nobody in there is actually coming up and saying, “What are you boys doing?”

Berton:

We got good and pretty crazy access with the players. We’re shooting things during a spring training game off on the side. So I got to hang with Jesse Orosco and Dwight Gooden and some of the other real pitchers. Some of the young guys, Dykstra and Kevin Mitchell, were goofing around like, “Is this gonna be in the magazine?”

Horwitz:

We burned a hole in (catcher) Ronn Reynolds’ glove. They were “warming up” and we had a canopy up, and we burned a hole in his glove and that was the evidence.

Berton:

We were down on the beach, I’m in uniform throwing baseballs at Coke cans. That was kind of odd because anyone walking by, they knew the Mets were in spring training. So some of the people were thinking I was a real baseball player. We just played along with it. I said stuff like, “You might read about it later,” without having a clue how big a deal it was going to be.

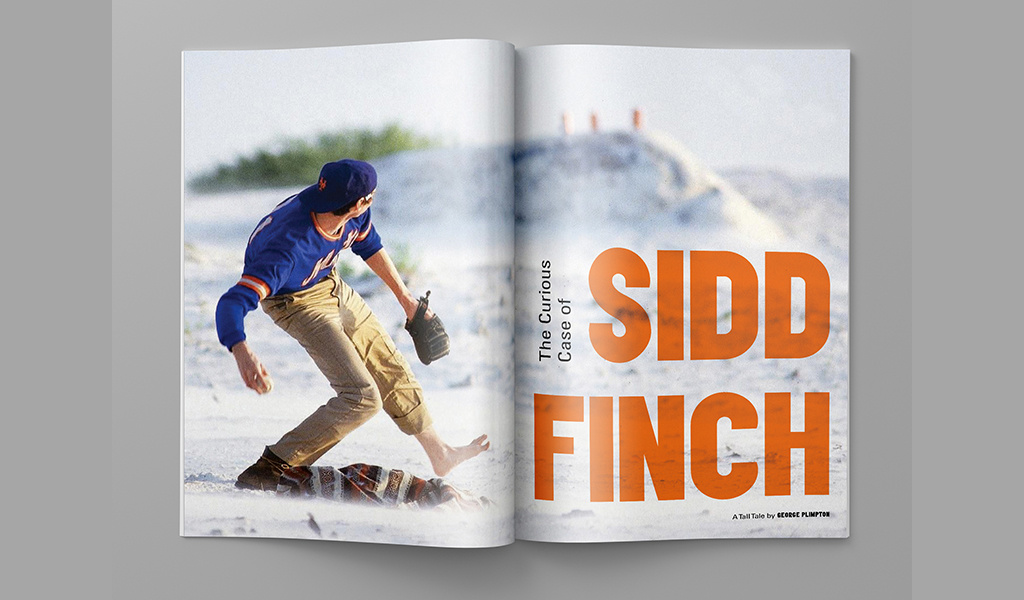

The shot from the beach became the famous opening image to the story.

Stewart:

There was something I didn’t like about that, and that was the one boot on and one boot off. I had shot that exact picture with two bare feet and with two boots on. I just thought the one boot on and one boot off, I said I think this will give it away. We don’t want to give it away on the opening spread.

Dee:

Between the time (Plimpton) submitted the story and the time it came out, he was in agony over the thought he’d gone too far. He thought, “Why does he wear one boot on the mound? Why the French horn? No one’s going to believe it. I took it way too far. I’m going to be a laughingstock.” It hadn’t occurred to me that even a really experienced, well-known writer might not be working in a state of total self-confidence all the time.

He wanted people to believe it. He was definitely committed to the joke. He wanted to fool people and he felt like if he didn’t fool people he himself would look stupid.

Stewart:

Nobody thought anybody was going to believe this. It wasn’t like we were sitting around thinking, “How are we going to put this over on the public?”

Berton:

Lane went back to New York and said the more he showed (Plimpton and Mulvoy) the different scenarios we got ourselves into, the more they loved it. And instead of having a small story, Plimpton had to flesh it out more. Lane even showed some of the vacation pictures from when we were together in Egypt — me on a camel. Plimpton loved all of that stuff.

The story ran over 14 pages in the April 1 issue. The first letters in its tagline — “He’s a pitcher, part yogi and part recluse. Impressively liberated from our opulent lifestyle, Sidd’s deciding about yoga — and his future in baseball” — spelled out “Happy April Fools’ Day — a fib.”

Dee:

(Plimpton) made a lot of money in those days giving speeches, and it so happened that he had a very longstanding commitment (the day the story came out) in South Carolina. He was going to be gone all day. So at some point, he broke it to me that I was going to be in charge. When people called up — if anybody called up — he just begged me to try to string the joke out as long as I could.

Stewart:

Nobody told the publisher, so when Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan called the publisher to ask if this was true, the publisher said, “It’s Sports Illustrated, of course it’s true.”

Horwitz:

The day the story hit SI, I got a call from a sports editor at a New York paper saying, “How could you give this article to Sports Illustrated? We cover you on a daily basis!” I said, “Listen, how you would feel if I gave a scoop you got to somebody else. I was honor-bound.”

Dee:

The New York Times guy in particular was like, “Come on, it’s a joke, right?” He said they’d sent somebody down there to look around and couldn’t find the guy. And I said, “Well, he’s notoriously press shy. It wouldn’t surprise me if he’s out of town because of all the attention.”

That was one of the amazing days in my life.

Berton:

I didn’t realize until one of the students had seen the magazine and was saying, “Mr. Berton, you’re not gonna be our teacher anymore? I didn’t know about this big baseball thing.” So after school I went to the 7-11, saw it on the newsstand and opened it up. That’s when I got my first glimpse of how big a story that was going to be.

Horwitz:

We kept it going for a good two or three days. Mel (Stottlemyre) was so good. The writers were asking him when Sidd is going to pitch, and Mel would say, “Well, we haven’t slotted him in yet. He’ll get his time.”

Berton:

Reporters were tracking Stottlemyre asking, “Where’s Sidd?” “Well, you missed him. He was here at five in the morning. Sidd’s already back in bed.”

Dee:

George was thrilled. It succeeded beyond his wildest dreams. It was national news. He was really excited — and relieved the joke had worked.

Stewart:

What made Plimpton’s job easy is that he had the permission of the owner to make up quotes, right? He’s got all these quotes from Stottlemyre!

When a kid reads the story, every single word, he reads about the French horn and the Buddhist monk and he says, “Hey, that’s a joke.” The professional readers, the paragraph about the French horn, you don’t care about that. You want to know what Stottlemyre thinks! I think that’s why people believed it.

It wasn’t just the gullible who believed it. It was plenty of people in journalism and in baseball.

Horwitz:

The beat writers were not really happy with me, because they got a lot of stuff from their editors: “How could you not get the story?”

Dee:

George Steinbrenner was furious. He couldn’t believe that Sports Illustrated had trashed its brand by publishing something willfully false. And it was really all because he believed it and probably fired a few scouts that hadn’t found this guy.

Stewart:

I’ll tell you one thing: (Commissioner) Peter Ueberroth told me that two major-league general managers had called him that night believing the story. That’s from Ueberroth’s mouth to me.

By that Thursday, the story had been debunked. The Mets invited Berton back down for the actual April 1 spring game, where Sidd Finch announced he wasn’t ready yet to pursue a baseball career. Berton’s one request was that he get to keep the blue No. 21 Mets jersey. He still has it.

Berton:

As I’m walking off the field, the Mets are warming up and signing autographs. Gary Carter’s right in front of me. And this kid is handing the ball Carter just signed to me, and I’m telling the kid he doesn’t want me to sign his ball. Carter comes around and goes, “Sign the ball, Sidd!”

Horwitz:

You couldn’t do what we did with social media. There’s no way we could do it this year. For two days, it was really good to be a part of. It was probably one of the most fun things I’ve worked on in my time with the Mets.

Stewart:

For a week, that was the biggest thing in America. A lot of people were trying to be upset about it. I don’t think anybody was really upset.

Berton became a celebrity, especially in his hometown Chicago. Plimpton eventually turned the story into a novel. Berton befriended longtime Cubs and White Sox pitcher Steve Trout when Trout was in line for a Plimpton book signing. He was invited to Sports Illustrated’s Sportsman of the Year banquet that year, riding in a limo with Earl Weaver and Brooks Robinson — “They were asking me about Sidd and I’m asking Brooks why Ron Santo isn’t in the Hall of Fame,” Berton said — and sitting at a table with honoree Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. He was honored with a “Sidd Finch Night” by the Brooklyn Cyclones in 2015. And he became close friends with Plimpton until the author died in 2003.

Berton:

It really is fun to revisit it. A real joy to the story was that if people did fall for it, they want to recount why with you and how great the story was. George just loved it. And once we met, we got along great.

Horwitz:

George Plimpton is dead, but I’m glad Sidd’s alive.